Alumni Resources

About the University

How Dr. Kester Phillips Never Let Failure Get in the Way of His Success

by C.L. Stambush

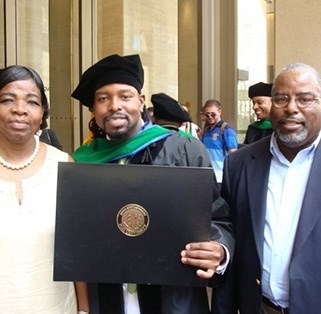

Before Dr. Kester Phillips '02 became a board-certified neuro-oncologist, and before he was accepted to a renowned medical school for a fellowship, and before he published dozens of articles in prestigious journals, and before he became medical director of the Ivy Center for Advanced Brain Tumors team at the Swedish Neuroscience Institute in Seattle, Washington, he was a biology student struggling with and failing every standardized test in his academic journey.

Before Dr. Kester Phillips '02 became a board-certified neuro-oncologist, and before he was accepted to a renowned medical school for a fellowship, and before he published dozens of articles in prestigious journals, and before he became medical director of the Ivy Center for Advanced Brain Tumors team at the Swedish Neuroscience Institute in Seattle, Washington, he was a biology student struggling with and failing every standardized test in his academic journey.

Not just once, but again and again. "These exams were my Achilles heel," he says. "I didn't know how to prepare for them to yield the necessary results."

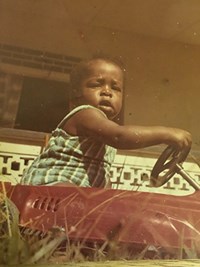

He might not do well with such tests, but Kester excels in overcoming adversity. An animal lover born in the Caribbean Islands of Trinidad and Tobago, he and his brothers were raised by his grandparents after his parents emigrated to the United States. They were divorced by the time he came to the U.S. at 14 years old to live with his mother in Brooklyn, New York, while his father had moved to Evansville.

"We grew up in an impoverished neighborhood, well below the poverty threshold,” Kester says. “In high school, I started barbering in the small living room of our apartment to earn money to help my mom pay bills and meet our basic needs. I perfected my skill by practicing on myself and my brothers. Still, I saw education as my path out of the struggle."

Kester's grades were good in high school, but his scores on the standardized SAT and ACT tests would not earn him entrance to college, even if he could afford it. As an undocumented student, he was not eligible for federal and state college scholarships. But, he was not deterred. He took a job, after graduating high school, barbering in a Brooklyn shop for two years to save up to become a veterinarian. While cutting hair, he hit the books, earning a veterinary assistance certification through a distance learning program. His father suggested he attend college in Indiana, where tuition was affordable.

He applied to USI and was accepted, but his subpar ACT and SAT scores meant he would be placed in remedial courses for English, math and composition.

Academic institutions across the nation have historically considered these entrance exam scores one of the strongest indicators of a student's educational success, prioritizing them over all other measures of a person's capabilities. But that line of thinking is waning. In 2021, the University like many across the country, adopted a test-optional policy for students applying to USI. "While test scores can be a helpful tool in predicting collegiate student success, some research findings suggest standardized tests do not accurately reflect academic ability and potential for success in college," says Dr. Mohammed Khayum, USI's Provost. "By adopting a test-optional policy, USI allows each student to determine how to showcase their academic ability."

In the summer of 1995, however, entrance tests were not optional, and despite excelling in learning and applying that knowledge in the classroom he did not score well, and it shook Kester. Faced with a counter-narrative concerning his academic abilities, he wanted to attribute the low score to being out of school for two years. But the real issue was only beginning to surface, and it would be a barrier to overcoming every milestone in his educational career.

Kester knew he could not go down this learning road alone, and he sought help from Academic Skills, knowing he needed exceptional grades to be accepted in any veterinary program. "I was really determined to succeed," he says.

It was there that he met another person determined to see him succeed. Academic Skills volunteer tutor Dana Brooke, who retired from Bristol Myers Squibb after working 26 years and wanted to give back to his community. "Kester was a wonderful experience for me. He was very mature and conscientious," Dana says. "I helped him with [math], organic chemistry courses [and physics], but he was an excellent student in the biological sciences, and I could not help him there."

The duo developed a bond that endures still, as day in and day out Kester's knowledge of the courses deepened with Dana's extra guidance. "Dana had a knack for explaining complex concepts," Kester says.

Dr. Shelly Blunt, Professor of Chemistry and Associate Provost for Academic Affairs, recalls Dana's dedication to Kester and all USI students' success as a force that motivated him to sit in on some of her lectures, to refresh his own knowledge and ensure his instructions aligned with her teachings.

While attending USI, Kester continued cutting hair (opening and operating his own shop) to support himself and his young family— a wife and daughter. His dream of veterinary school was redirected, however, when his advisor Dr. Jeanne Barnett, USI Professor Emerita of Biology, recommended he become a physician because of his caring nature, warm personality, reliability and intellect. "He was so good with people...his optimistic, positive interactions. We talked about what his options and possibilities were, and basically, it came down to the fact that you do much the same thing as far as the work that goes into getting into vet school and medical school, so why not broaden your horizons?" she says.

In his senior year at USI, Kester discovered Yale University's Minority Medical Educational Program (MMEP). He applied and was accepted, but still had three courses to take at USI to graduate. Barnett advised him to join the program and take his last college courses at a college in New York, then transfer the credits back to USI. "I remember riding the trains to take classes at Bronx Community College," he says. "The courses were easy after my education at USI."

Some things were a breeze, but getting into medical school would not be, as more standardized tests—MCATs— were in his future. During this time, he took a job as a tech assistant at one of Columbia University Medical School’s labs, caring for laboratory mice and rats before taking a position as a research technician in a laboratory studying the physiology and cell biology of neurotransmission in disease states, particularly in drug addiction and Parkinson's Disease. The research excited him, harkening to his molecular biology studies with Dr. Marlene Shaw, USI Professor Emerita of Biology. "Here I am," Kester says, "this is all the stuff I learned from her now being applied."

As a research technician putting in countless hours, he co-authored a few papers with his mentor, neuroscientist Dr. David Sulzer, presented his work at national conferences and more. After three years, it was time to apply to medical school. He took the MCAT and scored poorly. He took it again. Another low score. Again. Same story. "I think I took it four times," Kester says, "but it was a no-go to the point that one doctor at Columbia University said I'd never get into medical school. That was hard to hear, and it discouraged me, but it also motivated me to prove everyone wrong."

Kester started researching international medical programs, finding them less focused on test scores and more interested in his entire academic portfolio, his drive and his determination. In 2006, at the age of 32, he returned to his island roots when Ross University School of Medicine, in Dominique, West Indies, recognized his passion and compassion for others and invited him to join the Class of 2010. "I stayed focused," he says. "I had to make it work." He enjoyed neuroscience and cellular and molecular biology at Ross University. He even tutored friends who needed help in those subjects.

Ross University was a dual-campus program, with introductory science courses conducted on the island and clinical clerkships at hospitals in the United States. During his clerkship training, he rotated through different medical specialties and treated patients under the supervision of physicians. The rotations exposed him to all the general fields of medicine, including internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics/gynecology, psychiatry, neurology and general surgery. "Neuroscience was fascinating, so I wanted to study neurology," Kester says.

Kester returned to New York after graduating from Ross University to study clinical neurology at the State University of New York (SUNY) Medical Center in Brooklyn. Four years studying neurology, learning different subspecialties—stroke, epilepsy, neuroinflammatory disease, movement disorders, headache, neuromuscular disorders, pediatric neurology, behavioral neurology— led to one finding: none were a fit. "I wanted to block the oncogenic signal transduction pathways with drugs to retard tumor growth," he says. "I had memorized all these pathways in Dr. Shaw's Cell Biology class and in medical school."

His education was far from over, and Kester headed to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in Manhattan for an elective in brain tumor treatment. "While there, I developed an interest in the science behind tumors and cancer, as well as the art of treating patients’ brain tumors," Kester says. "In neuro-oncology you have the unique opportunity to interact with patients and their families throughout the entire trajectory of their disease."

Being there for others is who Kester is and he'd found where he could be his best. Now he needed a fellowship to take him to the next level. He applied widely and lined up interviews. His first was at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts. The director was impressed and offered him a coveted specialist fellowship in neurology at the end of the interview. His head encouraged him to keep interviewing, but the chair of neurology at SUNY Downstate said, 'Are you crazy?! Nobody turns down Harvard.' So, he accepted.

Before joining Harvard, Kester was required to earn his medical licensure. He marginally passed the first two components of the three-step exam and needed to pass the third to be credentialed for the fellowship program. During residency, he experienced some upheaval during a divorce and failed the board exam three times. That's right, another standardized test. By now, you know the outcome. "I called the medical director and told him I failed the board exam after my third attempt," Kester says. "Fortunately, he held a spot on the condition that I pass on the fourth attempt." He hunkered down for two months to devote 100% of his time and energy to passing the test. Still, it took four tries. By the end of his first year in the two-year fellowship, however, Kester had to admit the fellowship program was not a good fit. "I needed additional training to fulfill my career objectives," he says. "I looked for another opportunity to hone my skills."

Just like when Dana Brooke entered his life at USI, the stars were aligning to bring Kester a new mentor through a fellowship at the University of Virginia Medical Center alongside Dr. David Schiff. "[He] wrote the first neuro-oncology textbook I purchased [during residency]," Kester says. "I would see him at conferences and would be awestruck."

Just like when Dana Brooke entered his life at USI, the stars were aligning to bring Kester a new mentor through a fellowship at the University of Virginia Medical Center alongside Dr. David Schiff. "[He] wrote the first neuro-oncology textbook I purchased [during residency]," Kester says. "I would see him at conferences and would be awestruck."

Alongside Dr. Schiff, Kester absorbed knowledge, insights and advanced techniques. He conducted innovative research, wrote chapters for medical books and presented at neurological conferences. The rigors of the work infused his natural drive to push himself beyond expectations.

Today, Kester is a naturalized citizen and part of a neuroscience team in Seattle, Washington, specializing in brain cancer and living in a house overlooking Puget Sound. His daughter and son are grown and navigating their own college careers. His patient-centered philosophy reflects his inner self: compassionate, kind and respectful. His patients leave him five-star reviews on healthcare sites that rate doctors. And while in many ways he has arrived, his journey is far from over.

When he rode in the car to Indiana from New York to attend USI, he cried. When he reflected on the people who ensured he succeeded at USI, tears welled up in him. When he thinks of his patients an intense emotion squeezes his heart. "I'm there from the beginning to the end.

"I give them hope. I show them compassion," he says, noting he is always optimistic that new treatment options will emerge and improve the survival of patients with some of the most aggressive brain tumors.

"I just want them to live another day. It's a tough journey."