Alumni Resources

About the University

By C.L. Stambush

There are certain expectations in life—among them the right to clean water, a sanitary environment, and personal safety. Yet of the seven billion people populating the world, 2.5 billion don’t have access to them. Heather Deal ‘03 wants to do something about that, and she’s starting with a reinvention of the toilet.

Deal didn’t set out to be in the business of human waste, although in the year and a half since founding Santec LLC, a company that uses technology-based solutions to address sanitation issues, she’s grown confident in her ability to build a business and a future in the industry. Santec is the second problem-solving startup she’s initiated since graduating from the University of Southern Indiana with a degree in public relations. The first was a consulting group she operated for three years with her husband Jeremiah. Before that, both were employed in traditional jobs: he worked for Toyota, and she was a grants program manager for Goodwill Industries.

As an entrepreneur, Heather knows it takes determination and confidence to be successful – and if you’re not willing to put in the hours you can’t move forward. But when Jeremiah found the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s Reinvent the Toilet Challenge online, Heather never imagined the career change ahead. At the time, their consulting group was growing, but Jeremiah wanted a side project that tested his engineering talents. “He’s a curious person and thought he could do this,” Heather said.

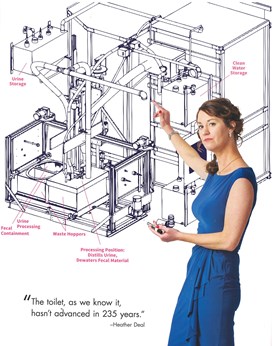

"The toilet, as we know it, hasn't advanced in 235 years." - H. Deal

Although he had 15 years of experience in engineering and manufacturing, he had no background designing toilets, and neither of them knew anything about public sanitation. To learn, they returned to the Internet. “It’s the new library,” Heather said. “We learned so much about sanitation and the challenges so many face. Most Americans don’t consider the issues.” While the Deals have three toilets in their house, 40 percent of the world’s population must use community toilets or an open field.

The Gates Foundation is out to change that. It offers grants for inventive ideas that meet lofty aspirations. The reinvented toilets must remove germs from human waste and transform it into valuable resources such as energy, clean water, and nutrients; function off-the-grid; and operate on less than 5 cents per user per day.

Jeremiah sketched out an idea on a legal pad in their living room and Heather transformed it into a 100-page grant application. “At the time, the Gates’ challenge was only open to non-profits,” she said, “but we didn’t know that.” However, of the 435 entries, the Gates Foundation saw promise in their idea and they were invited to Seattle as “partners,” to lend expertise to institutions such as Stanford University, California Institute of Technology, and the University of Toronto, to help turn their ideas into realities. In the meantime, the Gates Foundation helped the Deals refine their concept.

“Our initial design involved liquid petroleum as the power source and we were asked to change it to solar,” Heather said. “It was a bit of a challenge, but when the Gates Foundation asks you to make a change, you do it.” Under a deadline, the Deals worked day and night. The project consumed their lives, and they wanted to be more than a partner. “We may have initially stumbled across the opportunity,” Heather said, “but we’re now chasing the challenge.”

Santec didn’t exist when the Deals flew to Seattle, but on the flight back a corporation was conceived when Jeremiah sat next to Tony Bell, retired sergeant major in the U.S. Army Special Forces and a contractor for the Defense Department as an occupation safety and health officer.

While in Seattle for the Gates’ challenge, the project’s program officer suggested the Deals work a military application into their sanitation system. After all, when U.S. troops occupy foreign lands they live by the conditions of the country. Sewer systems don’t exist in Afghanistan’s deserts where troops reside, but soldiers still need fresh water and toilet facilities. Water has to be trucked in, which is risky in war zones.

Bell’s 35 years of service gave him plenty of exposure to the military’s sanitation plights, and he was interested in finding a solution. His experience and connections were what the Deals needed to transform their idea into a viable business. Bell introduced them to retired Lieutenant Colonel Robert Castelli, a 20-year Special Operations veteran with experience ranging from strategic to operational to tactical in both the United States and abroad. With Bell and Castelli on board, the foursome formed Santec LLC.

“It’s important to know what you’re good at and what you’re not, and to enlist the help of others who can do what you can’t. Surround yourself with problem-solvers.” - Heather Deal

In 2012, the Gates Foundation widened its acceptance pool and considered proposals from for-profits. Santec emerged one of the top three grant recipients in 2013, and was awarded $719,658. The other two were Unilever PLC, a global conglomerate that boasted sales of more than $85 billion in 2012, and Duke University, a top-tier research institution ranked as the seventh-best college in the United States by U.S. News & World Report.

To say Santec is the underdog is an understatement. It’s a four-person company operating out of Newburgh, Indiana, that hired a couple of engineers as consultants and a local fabricator to construct their GF-1 prototype. In eight short months, they transformed their concept into a working waterless toilet using “off-the-shelf components.” GF-1 (constructed inside a 20-foot shipping container) separates human wastes, converting excrement into pathogen-free biochar (charcoal) and urine into drinkable liquid via a heating process operated by a laptop computer and powered by three 20 x 8-foot solar panels.

As grant recipients, Santec’s prototype would be evaluated for proof that it does all it claims once it arrived in New Delhi, India, for the Gates Foundation’s Reinvent the Toilet Fair. To ensure it arrived in working order, Heather consulted with a maritime specialist on the best way to ship their toilet. She was advised to deconstruct it and ship it in sections. “We videoed the unit processing waste so we’d at least have something to show in case it became damaged in transit,” she said. “I hope for the best but prepare for the worst.”

Because the unit could be used in India, Heather said they were sensitive to cultural differences. For instance, Indians prefer to squat rather than sit, so Santec’s unit has footplates built into the bench that forms the seat.

She’ll travel to India a week before the Reinvent the Toilet Fair with Jeremiah and two others. They’ll reassemble the unit in India and it will be transported to the Taj Hotel, the site of the event, where it will be displayed along with 15 other reinvented toilets.

Jeremiah may have had the engineering insight for a sanitation system, but it takes leadership for a company to prosper, and that’s all Heather. “Being a small business owner, I wear lots of hats,” she said. “On any given day I meet with bankers, lawyers, or accountants. I consult with the engineers we contract, and regularly talk to our partners at the Research Triangle Institute (RTI) and Duke University. I work 80 hours a week, pushing myself far harder than I would if I wasn’t working for myself.”

Heather and her team work hard, but they don’t work alone. Collaboration is key in the challenge, and Santec partners with Duke and RTI. Heather confers with scientists at both institutions, communicating ideas in a community of PhDs.

Duke tested the results of the GF-1 and gave it a clean bill of health. “I am pleased to inform you that the trials with real human liquid and solid waste have been proven pathogen-free by my colleagues,” she said.

“If I’m going to guarantee the outcome is safe enough to drink, and encourage others to do so, I should drink it myself. I would be confident to drink [the urine] in the future.” Heather Deal

Santec’s GF-1 toilet costs $400,000 to engineer and build, although future costs will be greatly reduced as the engineering is refined. The unit, however, is more than an expensive self-contained waste management system. It provides dignity, privacy, and personal safety for women and girls in third-world countries where, due to isolation, rape is a problem associated with open-latrine environments.

In terms of military and disaster applications (such as the Super Dome in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina), GF-1 would be a blessing, but when it comes to promoting a change in countries like India, Kenya, and China, it’s daunting. Perceptions must change. “We have to make owning a toilet a status symbol like a Louis Vuitton purse,” Heather said (paraphrasing Jack Sim, a.k.a Mr. Toilet, an international social advocate). “I have a toilet, so I’m somebody.”

Santec’s concept has elements that help it gain acceptance and shift perspectives. Its solar panels allow the waste management unit to operate as a cellphone charging station. The Internet signal, designed to inform an operator within a 10-mile radius when the solid waste basket is full and safe for humans to handle, also provides Internet access to remote areas. In a world of haves and have-nots, it will make a difference. “This challenge opened our awareness,” said Heather. “We ought to be able to improve the lives of others. We’re going to get there.”

To see pictures of her work, visit https://threebirdswan.com/new/

Impact of Improved Toilet Design:

1.2 billion people live without clean drinking water. 90% of surface water in India is contaminated by feces.

Women spend 200 million hours a day collecting water.

1.8 million people die every year from diarrheal diseases. A child dies every 21 seconds.

More people have mobile devices than toilets.