Alumni Resources

About the University

by AmyLu Riley '93

“You do not have to define yourself by your own challenge. Your physical challenge does not have to be limiting to who you are or how you fit into the landscape of your own community, in your own world.”

Sara Beth Vaughn '11 M'12

Sara Beth Vaughn’s feet have a lot to say. They tell an important part of her lifelong story of hope over hopelessness, one that began the moment she was born, three decades ago, and failed to take her first breath.

Due in November but born in August, alumna Sara Beth’s life began as a fight for survival. As a premature infant with blood clots in her brain, she was not expected to live, or—if she did—to ever be self-aware.

She did live, however, and has become much more than self-aware. Even as an infant, Sara Beth— who now enjoys karaoke and performing comedy at open-mic nights—was highly verbal, speaking in complete sentences by age one. But as a result of brain damage, she had spastic cerebral palsy (CP), a condition that affects motor development.  Because of CP, her leg muscles were permanently contracted—crooked legs was the term she used as a child to communicate her condition. Her right arm, although normal in appearance, wasn’t functional. And her feet—“my not-so-beautiful feet,” she calls them—were so turned inward that her parents were told that she would likely never walk.

Because of CP, her leg muscles were permanently contracted—crooked legs was the term she used as a child to communicate her condition. Her right arm, although normal in appearance, wasn’t functional. And her feet—“my not-so-beautiful feet,” she calls them—were so turned inward that her parents were told that she would likely never walk.

At a young age, she felt hopeless in the face of all the dim prognoses she heard doctors giving her parents—dismal prospects about everything from walking and cognitive ability, to independent living. “As a child, you have ears,” she says. “It disheartened me.”

But then came social services and Shriners Hospital. Social workers helped her replace can’t with hope, and surgeries physically changed her. Pegs implanted in both ankles held her feet straight, and surgeries to lengthen her Achilles tendons brought her feet down flat, instead of on tiptoe. Other treatments to straighten her legs weren’t successful, but with the changes to her feet, she could now learn to walk, at age 5, for the first time with a walker. But when Sara Beth began elementary school, she stopped using her walker. “Out of stubbornness,” she says. “When I realized that none of the other children had a walker, I decided right then and there I wasn’t going to use mine anymore.”

After many falls, for which her parents endured some criticism, Sara Beth eventually learned to walk without a walker, using her stomach muscles to move her legs. Now, more of life that had previously seemed out of reach, such as driving, living independently and having a career, seemed possible.

Impossible is not a fact. It's an opinion. Impossible is not a declaration. It's a dare. Impossible is potential. Impossible is temporary. Impossible is nothing.” Muhammad Ali

Inspired by her childhood social workers, Sara Beth became one, earning both a bachelors and masters in social work from USI in 2011 and 2012, respectively. She spent the first five years of her career at Aurora, Inc. in Evansville, serving as an assessment specialist, providing empathetic crisis diffusion and counseling to people experiencing homelessness; then she was a development specialist, focused on grant writing, program renewals, reports, performance measures and public relations. She’s been social worker for the Vanderburgh County Health Department, too, where she helped people navigate their medical diagnoses and treatment choices, while seeking “to understand the why behind the what” of another person’s situation. This kind of compassion is healing, she says, for others and for herself.

From her own experience, Sara Beth knows the importance of hope in difficult times. That’s why she’s begun a new path as a public speaker, sharing her message: You can. While she loved her life of local service, she’s dedicated to expanding her reach: “I would like to be, at some point, an international speaker and author,” she says.

Sara Beth’s words tell another part of her story that can’t be told just by seeing her feet—or her legs, or the rest of her petite body. And this inner part of her story gets complicated, because it’s not easily reconciled with the visible reality. She talks about there being “no limits,” and about the power of the words I can. “I think when you’re told, ‘No,’ and, ‘You probably won’t,’ and, ‘You probably can’t,’ you kind of take on the attitude of, ‘Yes, I will, and I don’t need anyone’s blessing to do it,’” But she’s so pragmatic about her actual limits and what she can’t do, that there seems to be a contradiction between the story that her physical body is really experiencing, and the story that her spirit—expressed in her soaring words—would like to be true. For alongside her many successes and accomplishments, and a very full life, some doors have remained closed to Sara Beth because of physical limitations.

Her legs are still permanently, painfully bent, making many activities unsafe or impossible, and she lives with severe arthritis. She would have liked to have done the outreach type of social work, visiting people in their homes, but that was ruled out because she could require physical assistance—like navigating stairs—when help might not be available. And she would have loved to have joined the military; she craves service, structure, exercise. Although she uses a treadmill every morning, set on the highest incline to give her contracted leg muscles more of a workout, balance is always a challenge. She needs the handrails, so she can’t ride a bike. She recalls with visible joy, however, how her family has always encouraged her to try things: “They bought me a bicycle when I had walking casts, and I could sit on it, and I had dreams of riding that bike,” she says. “That was something the doctors could have told me up front--that balance is not something you can acquire, no matter how much you practice.

“I don’t like admitting limitations,” she says, “but in truth they are there.” And that’s the crux of the seeming contradiction of Sara Beth’s I can and her I can’t. She has found immovable obstacles in her life. However, it is equally true that she has seen the boundary line of can’t move before, and who knows when or whether she or someone else might be able to push that line again, with the right hope and help.

Every statement Sara Beth makes about her identity, her life, seems tied in some way to the experience of living in a body that has weighed in so dramatically on her options, and, in doing so, has made her so empathetic to other people experiencing life’s challenges. So it is a puzzle when she says she wouldn’t speak about her physical limitations unless asked direct questions about it, yet readily describes herself to others through the lens of the physical disability they see (her LinkedIn profile leads with her cerebral palsy). Is this a contradiction?

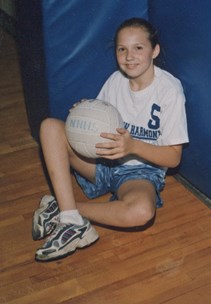

No longer the insecure child at the New Harmony, Indiana, pool trying to hide her feet, Sara Beth is now proud of the outwards signs of CP and says she mentions it as a way to take down barriers and helps others connect with her.

Clearly, this is a complicated dance, this two-step between her tiny body and her towering spirit. It reflects the ratio in which her formation has taken place—the fingers of circumstance molding her versus her breaking, or else accepting, each limitation. And that’s the part of the story her feet cannot fully tell; the story to which her bent legs have contributed at every turn.

If you enjoyed this story, let us know at magazine@usi.edu.