Alumni Resources

About the University

by C. L. Stambush

An Elephant of a Story and One Woman’s Quest to Tell It

At times it’s difficult for Erin (Johnson) Gibson ’96 to talk about the main subject of her documentary, even though the two never met and the differences between them are as vast as an ocean, except when it comes to three things: intelligence, long memories and emotions. The final is evident in the way Gibson’s voice cracks and her eyes well up with tears when she talks about the life and death of Kay.

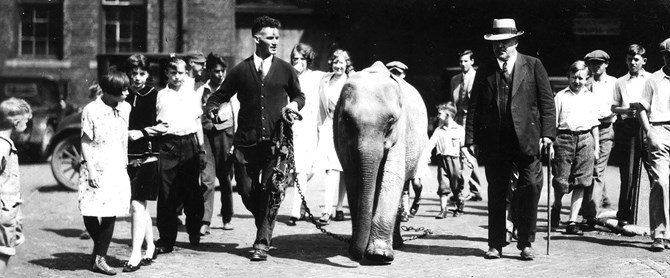

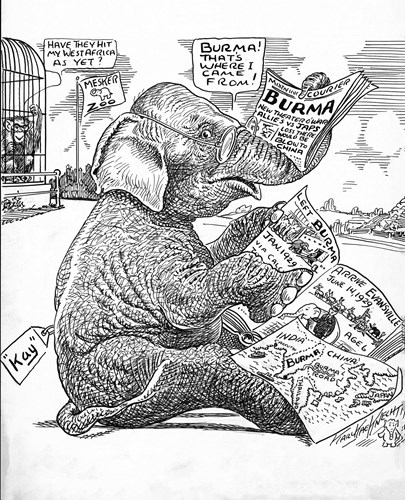

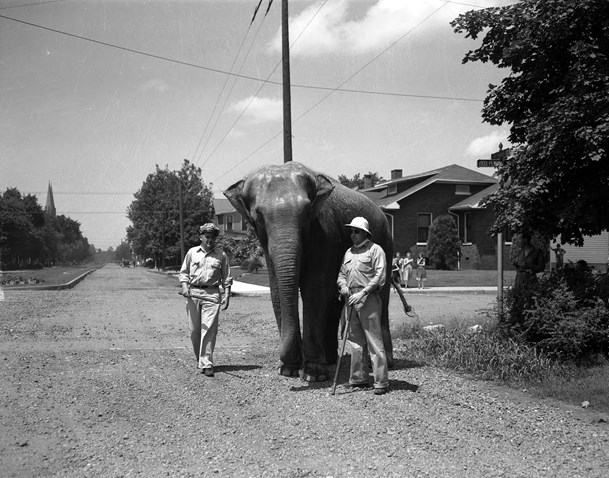

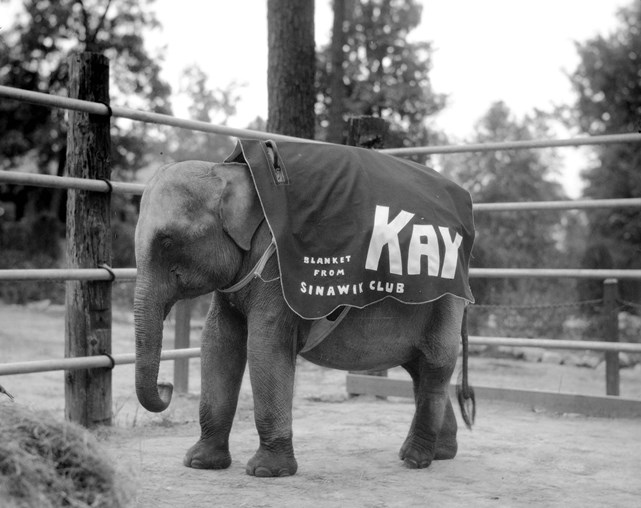

Kay was Mesker Park Zoo’s first pachyderm, delivered to Evansville in 1929 at the age of 6 after being captured in a Burmese jungle, more than 8,000 miles away. Crated and loaded on trains and ships, eventually arriving in Evansville, Kay’s journey was chronicled and heralded by Karl Kae Knecht, a journalist and cartoonist for The Evansville Courier from 1906 to 1960, who roused citizens’ interests in her impending arrival with his “letters-from-Kay” series, and his daily, front-page political cartoons. People talked about her and school children campaigned for pennies to help raise the necessary funds—$2,750—to buy the wary-eyed, 1,500 pound baby.

“Evansville was enamored with her. Then, they forgot about her,” says Gibson, 63 years after Kay was banished from the city for killing her trainer and zoo superintendent Bob McGraw in 1954. “And it hurts."

An animal-lover, Gibson knew the story about the zoo’s first elephant, but she didn’t become obsessed with discovering what happened to Kay after the city sold her for killing McGraw until she heard a horrendous story on the radio in 2009 about Kay’s demise, involving a box truck with a hose affixed to the exhaust. “It was just an outrageous story that stopped me in my tracks,” says Gibson. “My first thought was, ‘That can’t be true, can it?’”

The veteran radio journalist and USI instructor of journalism’s journey to learn what happened to Kay began by investigating the rumored execution—a story made worse by the report that Kay’s body had been left at the end of a dead-end road. “I’ve never been affected by a story like I’ve been affected by Kay’s story,” says Gibson, noting the times could be brutal for captive elephants. “I knew, whatever her outcome, it couldn’t be good.”

Gibson’s search for Kay began with her fingertips. Plunging into the internet—Google the word elephant and you’ll get more than 98 million hits—immersed her in “bread crumbs” and dead ends. One mammoth site in particular was riddled with dubious sources that left her in a sea of uncertainty. “The more I dug into [the] information, the more I realized [the site] really was citing unreliable sources,” she says, because it presented memories and commentary as fact.

For three years, she sporadically hunted for reliable, original sources detailing what happened to Kay after leaving Evansville, bookmarking on her computer the scant information she uncovered. Then, she discovered a local database containing digitalized and archived articles of The Evansville Courier and Press—dating back to 1875—that contained the first clues to Kay’s death. “Suddenly, everything opened up. Here was a searchable database where I was able to type in the words “Kay” and “elephant” and everything came up,” Gibson says. “That’s when the real work began; [before] it was just curiosity.”

Sitting at a heavy oak table at Evansville Vanderburgh Public Library’s West Branch, Gibson discovered, in the database, a news brief from 1955, reporting secondhand that 32-year-old Kay had died four months earlier. The five-ton pachyderm, labeled a “killer,” had been sold and resold and was being transported from Texas to Michigan when she died en route.

Mid-century journalism differed from the way Gibson now teaches her USI journalism students, and the report contained few facts and gave her little to go on—just the vicinity in which Kay died and the names of a few people mentioned in the article. Gibson began tracking them down, leading her to drive to Michigan with her husband, fellow journalist John Gibson, news director for local public radio station WNIN, during USI’s 2015 spring break.

While on vacation, they visited a tiny newspaper office, plowed through reels of microfiche in little libraries and dug through cramped basements of county archives. “It was like being a detective,” she says. “It was so much fun to try and take every bit of information and triangulate Kay’s story. At one point, I was standing on top of a filing cabinet pulling down these dusty, giant plat books that were almost falling apart.”

Gibson’s documentary is an homage to Kay, as well as to Bunny, the elephant that replaced Kay at the zoo. “It’s really a larger story I’m trying to tell,” she says. “Even though I’m very focused on this local zoo and these two elephants, I’m interested in telling the story of elephants through them: How smart they are; how emotional they are; how long their memories are.”

Kay and Bunny’s stories are a parallel in Gibson’s mind, even though their endings were dramatically different. Bunny was a gentle giant people loved, who was reluctantly retired to an elephant sanctuary in Tennessee, where she lived out her final days with other elephants and slept under starry skies. “I think it’s hard telling Kay’s story without telling another story with hope,” says Gibson, “because I don’t feel like Kay’s story is cheerful in any way.”

While Gibson wrote, directed and produced her first documentary in graduate school—it won a national award—creating Two Elephants presented a steep learning curve, since film editing isn’t her forte. “I can edit a radio doc so quickly; I feel like I can do that in my sleep,” she says. “This has been an effort. The video is just a beast. Thinking in terms of ‘What is this going to look like?’ That, and how slow I’ve been, is just ridiculous.”

Although Gibson began the project solo seven years ago, she isn’t going it alone now that the research is done. She hired David Arthur ’16 while he was still a USI student to be her extra set of eyes, ears and hands. He operates the camera while she conducts the interviews, and together they fret over lighting and sound. “It’s just David and me,” she says, “and David is doing most of the heavy lifting.”

To tell both elephants’ histories cinematically, Gibson desperately needs film. Both the lost tapes and 8mm reels of Kay and McGraw at Mesker Park Zoo, as well as B-roll from the elephant sanctuary Bunny was at; footage to splice in between segments of the people she’s interviewed. As of yet, she has neither, despite a wealth of help from local zoo officials, television stations and newspapers, and community members, such as Mark Fisher ’90, who discovered some overlooked WEHT-TV footage, reporting Bunny’s travel from Evansville to the sanctuary, that Gibson calls “a treasure trove.” But so far, all the images of Kay with McGraw are stills that Gibson discovered in the vast archive collections at Willard Library and USI’s Rice Library. “If I saw Kay in motion I’d break down,” says Gibson, “and I don’t know if anyone could console me.”

Two Elephants is not only an epilogue to Kay’s life, but Gibson’s way of metaphorically setting her free. “Her story isn’t mine to tell,” she says, “but I feel like I have an obligation to tell her story. She doesn’t have a voice. She was 6…years…old when she was pulled out of a jungle in Burma. That’s going to mess you up.”

Gibson’s passion and perseverance for the project remains steadfast, despite people telling her she’d hate it by the end. But the tender-hearted animal lover still tears up listening to soundbites she’s heard 50 times, discussing Kay or Bunny. “I just don’t think it’s a story I’m going to lose interest in,” she says.

The story isn’t finished for Gibson, even though her documentary is almost ready for its fall 2017 release. She still doesn’t know where Kay is buried, indicating there’s more to her story. “I thought I knew, but it’s becoming more apparent to me that she’s not where I think she is,” Gibson says, her voice catching. “She’s very far from home. But of course, she always has been.”

Gibson’s Two Elephants documentary will air on WNIN-TV when it’s completed.

If you enjoyed this story, let us know at magazine@usi.edu.