Alumni Resources

About the University

by C. L. Stambush

On May 8, 1823, John Harvey and his wife were arguing with such intensity that their neighbor, Thomas Casey, wandered over to quell the quarreling. Harvey shot and killed him.

That’s one version. The other claims the two men were fighting over a woman and Harvey clubbed Casey to death. No matter what the truth is, both resulted in Harvey being the first person to be executed by hanging in Evansville, Indiana.

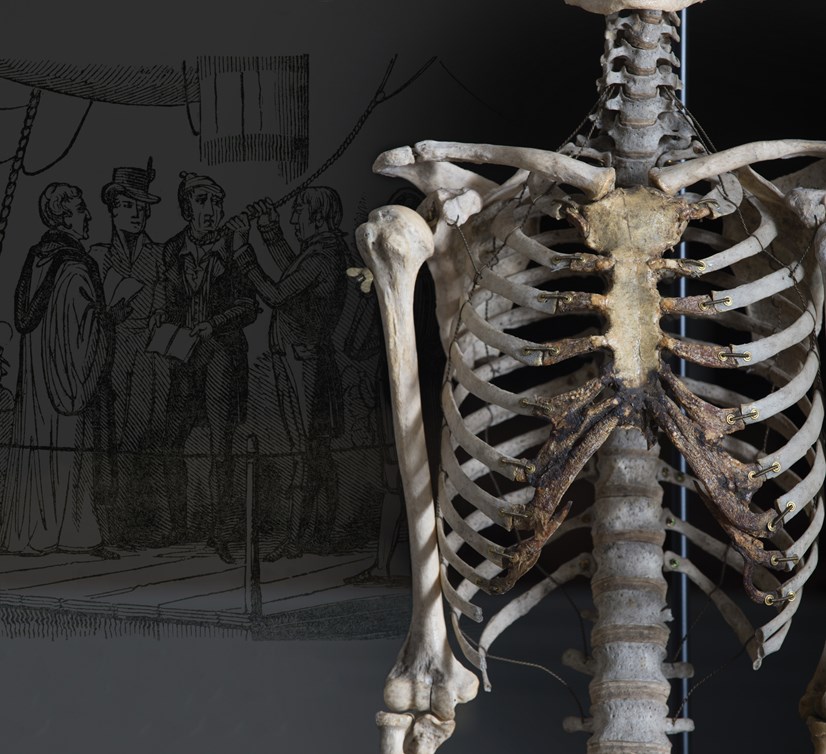

Harvey was buried at the corner of Main and Third Streets, only to be exhumed in the 1850s when a local contractor wanted to build on the site. During this time, medicine had become more of a scientific field, and, “…a physician whose office was [a] few doors down the street retrieved the bones, wired them together and… used them as a skeletal specimen in his office,” wrote Kenneth McCutchan, in an article for a folklore website titled The Boneyard: Evansville’s Intersection of Art, History, People, Culture and Ideas*.

What exactly happened to that articulated skeleton is a mystery, but in 1957, a skeleton, rumored to be Harvey, was donated to the Evansville Museum of Arts, History and Science where it became part of a display depicting a 19th-century doctor’s office until 2001, when it was put into storage. In the fall of 2016, Tom Lonnberg ’84, the museum’s curator of history, recommended it be gifted to the University to serve as a teaching tool, and it was immediately incorporated into the College of Liberal Arts’ Anthropology Program to be used in forensic anthropology and human osteology classes.

"There is a certain mystique to handling the real thing as opposed to a replica." - Michael Strezewski

“Since it’s a real person [and not a plastic cast], all the unique features of his life are there on the bones to see,” says Dr. Susan Helfrich, a forensic anthropologist who’s worked at USI since 2011 as an instructor and adjunct. “When students deal with that [real] skeleton it becomes clear that they are working with an actual person who used to live and breathe, love and have a life. That’s a much more powerful experience than dealing with plastic. They want to ‘meet this new person’ that’s in the lab.

The way students ‘meet’ this new skeleton (there are three human skeletons in the archaeology lab, but this is the only articulated one) is through science, because the story of whom the bones belong to is almost certainly not true.

“See this cartilage connecting the sternum to the rib,” says Dr. Michael Strezewski, associate professor of anthropology, pointing to what looks like dark brown bone, “that’s still there and it wouldn’t be if he was buried in the ground for a very long time. He would have been completely disarticulated, and any soft tissue like that would be completely gone.”

When Strezewski joined the faculty in 2006, USI offered little more than a cluster of anthropology and archaeology classes taught by cultural anthropologist Marjorie Jones, instructor in anthropology, who was at USI from 1989 to 2005. Over the years, USI has built a small but robust program that offers three major anthropological subfields: cultural anthropology, archaeology and physical anthropology, all taught by a staff of two full-time faculty and a stable of adjuncts who have doctorates in anthropology. “Without these quality adjuncts, there wouldn’t be a major because we couldn’t have offered the variety of courses necessary,” says Strezewski.

"Because we specialize in undergraduates, they will walk out of this program with more experience than most undergraduates elsewhere." - Michael Strezewski

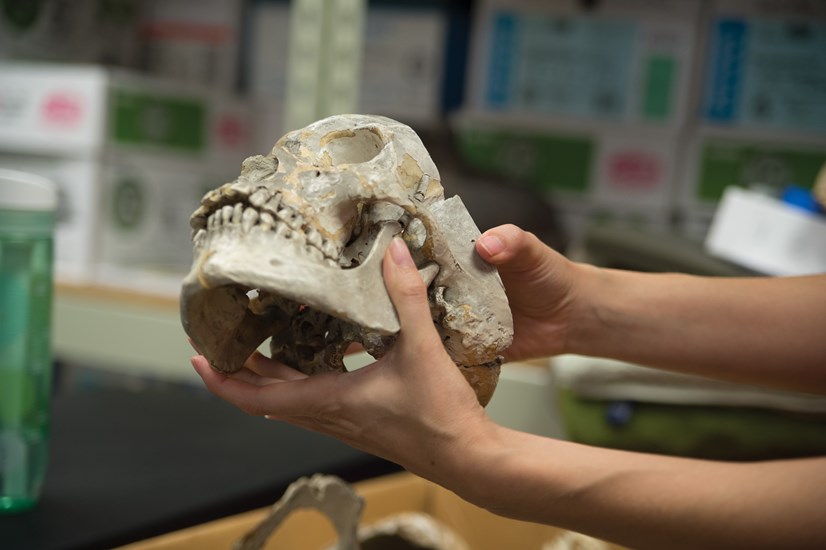

Forensic anthropology courses are an option for both physical anthropology and criminal justice studies majors. Through the analysis of physical markers on bones, physical anthropologists can establish sex, age, stature and ancestry. Abnormalities found on the bones can potentially show injuries and diseases—healed broken bones and medical procedures—as well as pathological conditions such as porotic hyperostosis (iron deficiency anemia) and cancer. Physical anthropologists like Helfrich assist law enforcement to help distinguish between human and nonhuman animal bones. In the recent case of Aleah Beckerle, a 19-year-old handicapped woman who was abducted from her bedroom in the middle of the night and later found murdered, Helfrich collaborated with the Evansville Police Department and Federal Bureau of Investigation agents to identify bones from a landfill, as well as those discovered by concerned citizens searching for Beckerle.

The mystery surrounding USI’s articulated skeleton, however, deals with questions of another sort: where it came from and who it was. Beyond the still present cartilage, the tell-tale signs of origin and identity rest in the presence of greasy marrow, the absence of soil and earthen stains, age, color, beauty, symmetry and teeth.

Helfrich hasn’t conducted a complete analysis of the skeleton yet, but her preliminary inquiries indicate some unusual findings. “The skeleton is an antique, and it appears to have parts from multiple individuals,” she says.

While the overall identity of the remains is suspect, Dr. David Glassman, a forensic anthropologist and former dean of the College of Liberal Arts, established some facts concerning it in 2008 when he conducted an osteobiography of the skeleton for the museum. He concluded that it was of European ancestry between the ages of 35 and 50 with a “living stature” of 5' 8" to 6' 1.5".

“The man executed was short, but this skeleton appears to be of normal height. Also, the man executed was potentially bellicose, so I would have expected to see healed fractures of the face and torso. But those were absent on this individual.”

Teaching students how to analyze a skeleton encompasses more than identifying markers on bones and comparing them with published statistics. Helfrich and her students discuss health, socioeconomics, ethics, cultures, religions and global views too.

When students examine the skull of the articulated skeleton, they see a thickening that denotes the presence of porotic hyperostosis. “That could mean he experienced malnutrition; it’s something seen on modern individuals who may have a lower socioeconomic status,” Helfrich says. “Since the person became an articulated skeleton, in class we talk about the path for that. Was he an unclaimed body—someone who didn’t have family to either claim him or pay for his funeral? That really hits the students pretty hard, because they have people who love them; people who care for them; people who they call every day; people who look out for them. A lot of the students are sheltered from issues of poverty or substance abuse or homelessness. In many cases, that’s exactly what they’ll be dealing with—people who are living on the fringes of society. Their bodies are the ones that tend to not be found immediately after death.”

Lack of identity can be hard for many students, who want to personalize the skeletons. “They want to name the skulls and skeletons that they come in contact with, and I have to tell them not to,” says Helfrich. “I have conflicting feelings on this because in some way they understand that this person had an identity and they want to refer to them. But in the field, professionals don’t do this because the idea is that the skeletonized decedent actually does have a legal name, and the nickname chosen by the students for them might not be appropriate.”

Skill is borne out of practice, and students in the forensic anthropology and human osteology classes are exposed to a variety of human skeletons so they can learn to discern differences in biological identities. Aside from the donated articulated skeleton, there’s a disarticulated one Glassman purchased from a medical supply company when he was a faculty member (it’s composed of male and female bones, presumably from India), as well as one Helfrich purchased on eBay that the seller claimed was female (he’d named it Lucy) who turned out to be an adult African American male. “I set out parts of the skeletons and have the students estimate sex and ancestry. It’s really interesting to watch as they find out that this one isn’t a petite female but an African American man,” she says.

When using the remains from India, culture is discussed alongside markers, and when using a plastic child’s skeleton, the discussion includes ethics. “Students don’t like to learn on plastic, but I say to them, I could have purchased a real 5-year-old’s skeleton but I didn’t think that was respectful,” Helfrich says. “That makes them think.”

Bones analyzed by a physical anthropologist not only determine a person’s statistical categories and how they died, but tell a story about the society in which the person lived as well. “It’s reflecting back on conditions of life that we might not think about,” says Helfrich. “It’s looking at the bones as individuals with individual stories that we can piece together [to help determine] what happened to that person.”

Piecing together the past of the person behind USI’s articulated skeleton is elusive, but Helfrich thinks it’s unlikely to be John Harvey. “This is a very professionally done articulated skeleton, and it’s not something cobbled together by an amateur collector,” she says. “It’s a common practice among people who articulate skeletons to use pieces and parts from multiple individuals to make the skeleton look perfect. That’s the idea; they want it to look beautiful. The question for me is, ‘Could this be someone who willingly gave his body to science?’”

If that was the case, then perhaps this specimen has always been a part of education. But despite its murky past, its future is clear. It will continue to be used to teach students for years to come.

*John Baburnich, USI’s student records data manager, produces the online journal.

If you enjoyed this story, let us know at magazine@usi.edu.