First Takes with Matthew Guenette

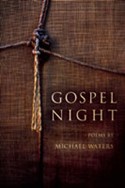

Gospel Night

Gospel Night

What is the work of a title? I was caught on the edge of this thought after reading Gospel Night, the tenth and most recent collection of poems from Michael Waters. Is the “gospel” in question one half of a compound noun—gospel night—conjuring the idea of a particular evening where truth is called down? Is it an adjective describing night itself, suggesting truth arrives in darkness?

Questions like these can form the high-wire act of reading poetry, and when they do, language and meaning are reinvigorated with a de-familiarizing resistance. The poems in Gospel Night—frequently formal, frequently situational, primarily narrative with moments of lyrical intensity—enact this resistance in traditionally poetic ways, namely through diction and form. Here for instance is the opening to “White Stork,” the poem that begins Gospel Night:

Such jazzy arrhythmia,

the white storks’

Plosive and gorgeous leave-takings suggest

Oracular utterance where the blurred

Danube disperses its silts.

Then the red-

Billed, red-legged creatures begin to spiral,

To float among the thermals like the souls, wrote

Pythagoras, praising the expansive

Grandeur of black-tipped wings, of dead poets.

Most Eastern cultures would not allow them

To be struck, not with slung stone or arrow

Or, later, lead bullet—

birds who have learned,

While living, to keep their songs to themselves,

Who return to nests used for centuries,

Nests built on rooftops, haystacks, telegraph

Poles, on wooden wagon wheels placed on cold

Chimneys by peasants who hoped to draw down

Upon plague-struck villages such winged luck.

The situation is clear. A single consciousness—a speaker observing storks—relates the bird through a sweep of contexts, beginning with a comparison of the stork to the poetics of meter and sound: its arrhythmic movements, the plosivesound of its feedings (plosive refers to stop consonants; think of the word “blade,” what your tongue does with the “d” sound ceasing airflow to the vocal tract).

The attention here to diction—arrhythmia, plosive, oracular utterance—is really an attention to the history of a word, its denotations and connotations that, as Lyn Hejinian says, “rarely coalesce…rarely come to terms.” The effect of this sonic beauty is a tension born from the rich possibilities of relationships between meanings. This choice—to provoke tension from diction and evoke the complexities of a word’s history—is one that Waters makes in nearly every poem, and one of the reasons to read them.

If diction and form make music of history, then Gospel Night divides its song into four parts, a move that will force readers to determine what motifs skirt the poems attending to each section. Such a choice can add to the complexity of a book—slowing it down rather than quickening its pace, suggesting a narrative arc—and this may well be the case here. The poems in Part I, because they introduce us to the formal and historical concerns the poet will pursue through the rest of the book history, perhaps suggest both how to read the rest of the book and what to read for. The poems in Part II might best be described as a brief history of violence, but as most of that violence is worldly and warring in nature, this section is complicated—and perhaps made ironic—by the poems “Joyride” and “Descending Mt. Washington,” two windows into moments of violence from the narrator’s life that seem small compared to the large violence around them. In Part III, the poems hang together in a kind of portrait of the artist as a young man motif, a turn that moves perfectly into Part IV, where the poems, taking on more erotic and playful tones, suggest an achieved experience, wisdom, a choice that hedges for the hopeful despite a world of violence.

The idea of order, to echo Wallace Stevens, matters perhaps much as any to a poet. Order has always been the difficult problem and the equally difficult solution. When you note Gospel Night’s penchant for form, its efforts in poem after poem to unhurry time, you realize that what Waters has ultimately written is an act of faith in the idea that form is transformative: it allows us to hold experience like a thought, to hold up it to history in all its worry and wonder, and it offers us a moment to climb inside it.

A poem emblematic of this faith in form is “Dog in Space.” The poem opens with:

Friday nights on WINS

Murray the K counted down the Top Ten.

A boy who loved the idea of order—

All objects having their place in the world—

I recorded each hit, its spot on the chart,

Then rummaged for meaning in weekly lists

As solemn scholars combed Dead Sea Scrolls…

Once more we are with a single consciousness—a narrator remembering when he was a boy listening to a certain radio station—that moves the memory through several contexts: music, religion, that Russian dog shot into space. How the poem creates this movement is primarily through an association of descriptions. These descriptions culminate with the heartbreaking lines about the “canine cosmonaut” in orbit:

I could spot the spark of the satellite

Among mute stars, crossing the sky, then hear

The weak, unanswered bark.

The metaphorical transformation is stunning as the dog in space becomes a voice—and how can we not think of a god?—that the young boy believes he can hear. Like all of Gospel Night, this is a poem about listening and being listened to: it is in fact a poem about poetry. The narrator, “A boy who believed in the idea of order,” says as much. Perhaps this is the best reason to read Gospel Night: the poems, self-reflexive and fascinated with form, exist for themselves, and in their existence suggest that anyone can salvage from history’s infinite daily grind a voice that can summon us into being.