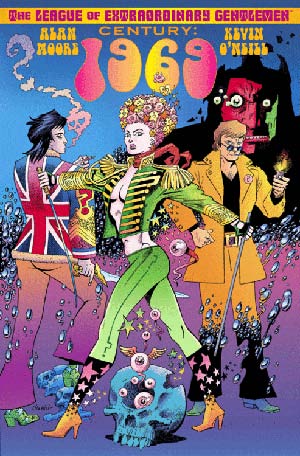

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Volume III - Century 1969

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Volume III - Century 1969

One of the rising arguments in support of the sequential art style popularized by comic books and graphic novels is not merely a genre of storytelling but a medium of its own. Supporters of this medium’s “neither fish nor fowl” approach to storytelling in the twenty-first century argue that it operates at the overlap between text and image that most relates to readers’ media relationship with the world. If you can absorb the internet, you know how to read comics, and if you can make comics work for you, you can become more savvy to the narratives of mass media, he has argued. In his textbook-slash-love letter to sequential art, Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud explains, in fact, how the majority of the work of reading the medium takes place in “the gutter,” the blank space visually separating any two frames. In the gutter between one panel in which a gun is drawn and a second where a figure clutches its chest, it is the reader who creates the thunderclap gunshot, the muzzle flash, the whip-pan tracking of a camera, the sense of surprise, the thud of impact, and the spray and then spread of blood. McCloud argues that only the reader can make any two logically unrelated images cohere into narrative. This interactive storytelling takes place multiple times per page of any comic book, with little of the expositional signposts on which film or traditional text are so reliant.

In discussing the methodology of sequential storytelling, critics and fans will inevitably reference Alan Moore’s body of work. Not only have some of his books been held up as benchmarks of the medium, but his major works of the 1980s (a cycle consisting of his collaboration with various artists on Miracle Man, Swamp Thing, Watchmen, and V for Vendetta) are given credit for reinvigorating the art and changing the demographics of who actually reads comics. He is also often marked as a high-water line before the appreciation of the more mature themes and styles he helped popularize inspired the following generation of writers, artists, and publishers to spiral down toward the lowest common denominator. Alan Moore is one of the creators both noted and blamed for making comic books “dark.” The revolution he helped inspired in plotting, content, and characterization within the medium has come to overshadow the still-remarkable efficiency he has at working so closely with an artist that the gutter is so enjoyable and rich an area for an reader to work, utilizing visual and textual leitmotifs to span the gaps between drawn panels as often as cause-and-effect or mere logic.

This is one of the reasons, perhaps, that The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Moore’s long-running collaboration with Kevin O’Neill, translated so poorly into a movie. Beneath the whimsy of its surface elements and central concept—characters from Victorian-era literature team up into a team of super-spies—there is a remarkable complexity to how the story can be read. Of course, Hollywood will find its own lowest common denominator and focus on action, décolletage, and special effects instead of committing to a Technicolor celebration of the very concept of British story along with what is now a thirteen-year mash-up of everything that Moore and O’Neill have learned about comic art experimentation.

Century: 1969 is the proposed penultimate book of the Century stories, following 2009’s Century:1910, and also of this rich collaboration, which has also included the first two complete series (the former relating the League’s defeat of a scheme by Moriarty and Fu Manchu; the latter, their actions during The War of the Worlds), and The Black Dossier, a multi-textual series of short pieces of the League’s twentieth century adventures which included, for example, one story in which On the Road’s Dean Moriarty—here, in the manner of the League stories, revealed to be a descendant of Professor Moriarty—fighting the shuggoths of H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulu Mythos stories, written in a loving pastiche of Keruoac’s voice. Part of the joy of modern comic book storytelling is the interconnected narrative built from decades of stories in a persistent world. An issue of a Batman comic this month will connect to last month’s but may also connect to a Superman story from 1957. A reader finds that knowing all of the stories benefits each new one experienced. Single stories may take years to tell, one chapter at a time. What Moore and O’Neill have done is to recreate that connectivity by hijacking all of fiction and placing those stories into the world of the League in a way that has roughly matches our own historical narrative, often by transposing historical figures with their fictional surrogates. So, Century: 1969 finds England still scarred by a World War II fought against its world’s version of Adolph Hitler, Adenoid Hynkel from Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, who brought Germany to power by turning it into the perfect, soulless city-state of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. The summer of love in Swinging London witnesses not the awakening of England from decades of conservative repression following the war but from decades of INGSOC repression because 1984 actually took place in 1948. One panel of this book involves a reverse shot of what a character is watching on TV and it is a vortex of references to Rolling Stones songs, the original The Flash comics, Flash Gordon serials, the deaths of Jim Morrison and Jimi Hendrix, and other references wrapped into a succinct, cruel pun as though they were all one and the same.

This density of context is what sets the League stories apart from their peers. The deceptively simple plot involves our heroes trying to stop Satanic magician Oliver Haddo from possessing rock star Terner during a concert at Hyde park. Except that our heroes are the gender-swapping Orlando who has been associated with the League since Spencer’s Queen Gloriana (a fairy who fills the space of our Elizabeth I) first formed the League; Mina Murray, whose life was extended by her assault by Dracula; and a chemically rejuvenated Allan Quartermain, each of whom have been assuming various personas to disguise their immoralities. They have also found the pop culture-influenced world stage alien to their hard-cover mindsets. Haddo, an avatar of Alestair Crowley from Maugham’s The Magician, has been possessing the bodies of all of the literary Satanic magicians of the twentieth century in turn as he jumps from body to body. Terner is blatantly Mick Jagger, or rather, both Jagger and a character that he was playing in the film Performance. Hyde Park was, of course, named after Edward Jeckyll’s alter-ego, who died fighting Martians in an earlier episode of this very story. And these are just the more obvious references. Every character, item, and concept is a mash-up of literary, cinematic, musical, or pop arts and each panel is chock-a-block with colorful references to stories the reader will recognize or that no one ever should. It is no wonder that a series of books has been published that does nothing but annotate these stories. What is fascinating is that the curator and editor of these, Jess Nevins, is able to make these annotations almost as fascinating as the books themselves. One rack of pornographic magazines in the foreground of one panel provides pages of annotations which lay out which character from which short-lived British comic strip is being referenced in each title.

What is splendid about the League series is how well this dense contextual referencing works in the gutter. O’Neill’s art on the series once most strongly evoked the cartoons from the Victorian paper, Punch, but here has come to incorporate the various caricaturing styles of Mad Magazine. Recognizing Michael Caine’s character from Get Carter based on O’Neill’s illustration adds much to the character called “Mr. C-,” especially once it becomes clear that the character is also filling the role of Moore’s own classic creation, paranormal investigator and professional bastard John Constantine. Mr. C- changes the progress of everyone’s plans for reasons explained in the text but also because he is a surrogate to so many British anti-heroes; in the Swinging London of Century: 1969, all British gangsters are meta-fictional avatars of the real world’s Ronnie Kray, the original British hard man archetype. The richness of this referential mélange changes based on what the individual reader brings to these scenes and the work done connecting them in the spaces in between panels. Mr. C- intervenes both for his own reasons and because of what he symbolizes.

Sequential art is a medium that contains the tools for endless stylistic experimentation, but its friction between narrative and sensory appeal make it work like poetry more so than prose. The concept of a reader’s complicity in making the gutter rich work is very close to the process to internalizing a poem in order to interpret it. One of the joys of Alan Moore’s career has been his own experimentation with the similarities between these forms and, with The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen series, he and Kevin O’Neill have created their own version of the symbolist modern poetry. With this latest, and penultimate, book, they have created something like the “The Dry Salvages” portion of T.S. Eliot’s The Four Quartets. There is a density and beauty to that poem that is internal and unique that expands exponentially the more closely you read the other three linked poems, the more you read of Eliot, the more you read of poetry, the more you read, and the more you are part of the world. Century: 1969 is a personal map through the art and culture of the last century that ruminaties on the erosive effects of cultural change and the personal debt individuals accrue when they try to keep up with modernity. In addition, it makes a powerful argument for the possibilities of its still-young medium.

Anthony Rintala, poet and master eclectrician, spent many years on the hard streets of the American South. He did not live there, he just spent his youth walking down them toward the library or any of a series of comic book spinner racks. The streets weren't all that hard, after all; the asphalt went gooey after the sun shocked and cracked the surface like a crème brûlée. Rintala walked alongside these gooey streets of the American South, reading something, complaining, and thinking about snazzy desserts. That’s how he became a poet.