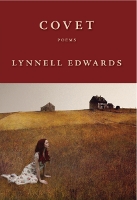

There is still a rusty, antiquated trap laid out against paternalistic readers approaching the work of a female poet looking for signs of “femininity,” “maternity,” or “fragility.” The jaws of the trap are held wide by the cultural artifice of this assumption: if she doesn’t embrace these traits, then she will make a clear point of rejecting them. It is a sad old thing, this trap, dysfunctional and dangerous mainly in its uselessness. What a shock then that Lynnell Edwards has whetted the teeth, oiled the hinge, and freshened the bait, turning rusted, creaking sexual politics into a real legbreaker. In Covet, femininity becomes a masterful force and fragility a pointed threat.

There is still a rusty, antiquated trap laid out against paternalistic readers approaching the work of a female poet looking for signs of “femininity,” “maternity,” or “fragility.” The jaws of the trap are held wide by the cultural artifice of this assumption: if she doesn’t embrace these traits, then she will make a clear point of rejecting them. It is a sad old thing, this trap, dysfunctional and dangerous mainly in its uselessness. What a shock then that Lynnell Edwards has whetted the teeth, oiled the hinge, and freshened the bait, turning rusted, creaking sexual politics into a real legbreaker. In Covet, femininity becomes a masterful force and fragility a pointed threat.

Edwards uses a beautiful and fragile central image throughout the poems: hard edges moving under, stabbing against, and sometimes puncturing a delicate membrane. In “Instructions for My Sons: Take A Jacket,” she depicts how “your boney wrists thrust / from the sleeves of that thin sweatshirt / will ache, and your slim frame / with no more padding than canvas / on tent poles will clench / with each honed breeze.” The gawky, young boy juts imperfectly out of, and against, his thin cloth shell in the same way that he is stabbed through it by the sharply “honed breeze.” Edwards takes a precise focus on that thin cotton barrier, rather than either the fragile boy or the threatening world that seek to tear through it. She builds on old themes of fragility and maternal care to create an image not just loving and delicate but also grotesque and painful. Elsewhere, she finds the same effect in many silent places: the bones of birds moving under too-thin skin or the crackle of ice skinning a surface and ready to shatter.

While she locates Covet's primary image in the “cutting edges” of the stars pressed down against the barrier of the sky and in the bones of shattered bike frames jabbing up against it, Edwards’ image most often reveals the delicacy of the body. At the end of “Instructions for My Sons: On Falling Asleep While Reading Hawthorne” staccato flashes churn in the mind of a child as he drifts to sleep as “the minister [and] the swollen joint” rage beneath the “sweet veil of sleep on [his] unmarked brow.” They are one and the same, bleeding into each other. In the first of the “Instructions for My Sons” series presented in this book, “Quit Leaving Your Bikes Out at the Neighbor’s House,” she clearly gives voice to this image,

This world steals.

Its bruising, indiscriminate want robs

the soft places, and wounds. And you—

left with rough sutures, scars,

place that aches in the rain—you

learn to live with what you can’t ever get back[.]

These poems present delicate bones, unformed beneath too little protection, “hard frames / screwed into a tangle of spoke and angle.” The want of the world doesn’t threaten something as soft as innocence; the wholeness of bones and the delicacy of flesh are threatened. Here the poems of Covet feel most similar to those of Laura Kasischke, in love with the terror of life.

The fragile horror of the unfed pregnancy in “Available Light” is the one explicitly focused image of a swollen belly pulling flesh too-taut over ribs and the protruding movements within, but it is an image that collates out of every hand and shoulder run through silk, every “jumbled wake of dull bones” presented on a silver plate, every ugly, sharp aspect of the world pressing against “pink, thin / curtains.” However, instead of reveling in the body’s fragility, Edwards more often creates the inverse, using this fragility of the body to make the world vulnerable. “After Making Love We Figure Out the Rest of the Day and Then Get the Hell Out of Bed” traps parents in an inverted pregnancy, on one side of a too-thin door, tangled in sheets, and the surly, unseen sounds of their son on the other while the tension of their changing relationships leaks through the barrier. Elsewhere, the breakable body haunts nature, as when turkey vultures gyre above “this green and ancient place, / dark hollow between the shoulders / of the soft-sloped ridge” to hunt “death and rot” in “Catharsis Aura.” In “Descent to Boathouse After Stroke,” the mixture of peace and suffering builds to the image of the drifting river’s “brackish skin of insect wings” mauled by hanging branches.

The implied violence of that quiet scene is repeated elsewhere. In “Triptych for Early Spring," section II, "Wound,” begins with the first annual burst of nature “pearling like blood // at the pricked end of a finger” and builds from this guiltless violence to the more directed threat of “the rose bush begging its necessary / violence, the brittle canes hacked into bloom.” The chilled tableaux of an abandoned lunch table in "Easter Monday" breaks into chaos when "a saw whines / its violence against the beam," lifting the poem into a frenetic pitch as sounds and colors collide and merge. “First, Hunger” then solidly connects this violence to maternity by viewing a child with an eye somehow at once predatory and protective. Its speaker states “I am your mother…who does not ask but knows your hunger” and notes “how night hollows your gut” before tucking into a savage sense of service, offering “melon cut from its green bone, / meat shaved.”

Edwards does so well at redefining these too-easily gendered concepts into shapes new and strange that the poems that merely repeat moments of this translation, rather than adding to the process, become missed beats. The poems collected as "from The Catalogue," each a small still-life of a curious bauble or kitchen item from an antique show, don't feel of a piece with the rest of Covet. Individually, they are fine poems but they feel like a tangent. The same is true of the first two movements of "Suite for Red River Gorge," the penultimate poem, which feel disconnected by simple narrative elements and blank description in its first two movements.

The third movement of this triptych, however, "Whistling Arch," does reconnect with the energy at the heart of Covet; it plays again with the blurring of hardness and softness. Here geological time is accelerated to reel the world madly through the aperture of the "lonely O" of a stone arch slowly molded by countless years of erosion, unspooling the past and future at once. "Whistling Arch" and the final poem, "Catharsis Aura," reveal a face of the natural world that is as loving as it is unsettling. Covet ends with the fragile beauty of a "matted thing of hair and claw and bone" watching the sky and mistaking the dive of a scavenger finding prey for a "wheeling fall" from grace. This is a book of “careful boundaries” and “snapped sheets” that luxuriates in moments when devastation presses so hard against the screen that it looks like glory from the other side.

Anthony Rintala, poet and master eclectrician, spent many years on the hard streets of the American South. He did not live there, he just spent his youth walking down them toward the library or any of a series of comic book spinner racks. The streets weren't all that hard, after all; the asphalt went gooey after the sun shocked and cracked the surface like a crème brûlée. Rintala walked alongside these gooey streets of the American South, reading something, complaining, and thinking about snazzy desserts. That’s how he became a poet.