by Adrienne Rivera

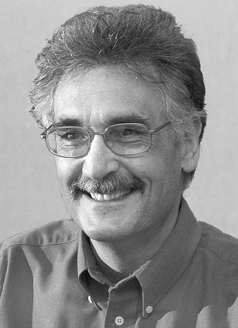

Michael Colonnese is the managing editor of Longleaf Press, a non-profit regional publisher specializing in contemporary poetry by emerging Southern authors. A professor of English at Methodist University, he teaches poetry, fiction, and screenwriting and directs the Creative Writing program. His short stories, poems, and essays have appeared in many literary journals, magazines, and anthologies, large and small. He lives in Fayetteville, North Carolina, with his wife, Robin Greene, and their two sons, Daniel and Benjamin.

Michael Colonnese is the managing editor of Longleaf Press, a non-profit regional publisher specializing in contemporary poetry by emerging Southern authors. A professor of English at Methodist University, he teaches poetry, fiction, and screenwriting and directs the Creative Writing program. His short stories, poems, and essays have appeared in many literary journals, magazines, and anthologies, large and small. He lives in Fayetteville, North Carolina, with his wife, Robin Greene, and their two sons, Daniel and Benjamin.

Adrienne Rivera: Congratulations on placing third in this year's Mary C. Mohr Nonfiction Award! I really enjoyed your piece and I'd like to ask you a few questions. Firstly, how do you decide whether an experience would make a better short story, nonfiction piece, or poem?

Michael Colonnese: I’m honored to be interviewed by Southern Indiana Review. To answer your question, I think the piece decides for me—which is really to say that I make such decisions on some less-than-entirely-rational-level of awareness. My poems seem to result from experiences that seem self-contained and metaphorically referential but which trigger images or language clusters that I haven’t quite understood yet. I often discover what a poem is about in the process of editing it.

Fiction, on the other hand, is my own strange way of imposing order on a world where almost any kind of experience is possible and everything seems interconnected. I often think of fiction as shelter from the storm.As for my creative nonfiction, well, technically speaking, it’s a lot like fiction with the self-imposed structure of truthfulness. I’ll allow myself to order things and to select details for effect but not to lie. In nonfiction, veracity provides added structure, much in the same way that the rules for writing a sonnet or villanelle can provide structure for a poem. Sometimes a better and tighter poem results if one works within set limits. But sometimes not. Sometimes experiences are simply too chaotic and ongoing to fit into either poems or nonfiction. “Bread” was right on the borderline. It was originally a much longer piece—I kept taking things out.

AR: So you're also a poet? I'm always impressed by writers who can work successfully in multiple genres. One of my goals is to try and become a better poet. What genres do you prefer? Have any poems or fictional pieces come from the experience described in “Bread”?

MC: Well, I guess I’m a poet. I just had a new chapbook, Temporary Agency, published by The Ledge Press. And I’m currently residing at a wonderful artist colony, Vermont Studio Center, where other people think of me as one. But I’ve never been able to write a poem about my experiences in the Bahamian out islands—where along with the terrible shipwreck described in “Bread,” all manner of madness reigned. I stepped on a poisonous sea urchin, for example, while bathing naked in the sea, and my entire foot swelled up like an inner tube. That ridiculous detail, for example, didn’t fit in anywhere, so I took it out.

AR: It sounds like quite an experience. “Bread” successfully spans a lot of themes like economics, mercy, and religion. What advice would you give new writers on approaching such weighty topics in their own work?

MC: I have the kind of mind that sometimes makes those kinds of connections, but I can’t really force such matters. “Theme” isn’t something I’ve ever consciously thought about when writing. These days, I teach college literature and writing courses for a living, so I do sometimes discuss thematic matters with my students, but I seldom think about theme in regards to my own work—not until long after a piece is done. Recently, I was teaching a short story, “The Guest” by Camus, to a group of freshmen, when I suddenly realized that my own piece, “Bread” had some similar existential elements. Wow, I thought, how cool. Frankly, when I teach young writers in my creative writing classes, I always caution them about labeling their work too early in the creative process. Call something a poem and you may feel the need to light a candle. Call it a short story and you may feel compelled to seek a quick conclusion and find yourself cutting a novel off at the knees. I’d much rather that all writers call their work in progress “stuff”—as in “this is the stuff I’ve been working on lately.”

AR: The imagery that appears in “Bread” is so vivid. How did you balance your description of the beauty of the island and the horror of the bodies and survivors?

MC: I’m not naturally adept at physical description so I make a conscious effort to include sensory detail. Since beauty and horror often exist side by side, if I can include the right details, the balance will generally take care of itself. After all, if I only noticed the ugly and absurd, I probably wouldn’t be able to stay sane and walk around. “I learn by going where I have to go,” as Roethke tells us.

Obviously when writing short nonfiction you can’t include every person or event involved, even if they are important. How do you decide what is most important to the story you’re trying to tell? I’ve always thought of literature as a kind of high-brow jelly roll. There’s a limited audience, and readers expect to be moved or entertained. Good editing requires that writers imagine themselves as readers. That makes it easier to be generous to your audience and take stuff out. Personally, I try to start with abundance and simply try not to be too shallow or redundant or boring or confusing. And sometimes that means I have to cut my favorite line.

AR: It seems like the events of “Bread” would stay with you for a long time and definitely have a lasting effect. Was it hard for you to write this piece? It’s such a multifaceted work—what do you want readers to take away from it?

MC: I’m a slow writer, and a committed one, but there are things larger than literature. “Bread” took years to get right, but if I learned anything from the events it describes, it was that there really isn’t any refuge—no tropical Eden to which one can return. Economic realities can often force hard choices. And only the very, very fortunate even get a chance to choose.

AR:So to go back to an earlier question, what "stuff" are you working on now?

MC: Well, I’m working on some stuff. I’ve got a handful of new pages with lines and stanzasthat really do look like they want to become poems and about two hundred pages of new prose that won’t stick to the facts and may turn out to be the beginning of a mystery novel—if I’m lucky.